It almost failed, our attempt to bring together partners from four continents on the southern border of Mexico around the World Refugee Day. On the way to the hotel, I receive the information that border officials are detaining the participants of Alarmphone Sahara (Niger) and House of Peace (Libanon) at Mexico City airport. Their mobile phones are confiscated, communication is cut off. Is this the end of the journey – a journey that began three months ago with visa applications that were only granted a few days before the workshop? Three hours later, and after our Mexican partners have intervened heavily, Moctar and Aida are free. We can start working. At the same time, we are shocked: two of our partners, who stand up for freedom of movement and the rights of migrants and refugees, almost became victims of a border regime that is increasingly repressive and openly racist worldwide.

Tapachula - "ciudad carcel" for people on the move

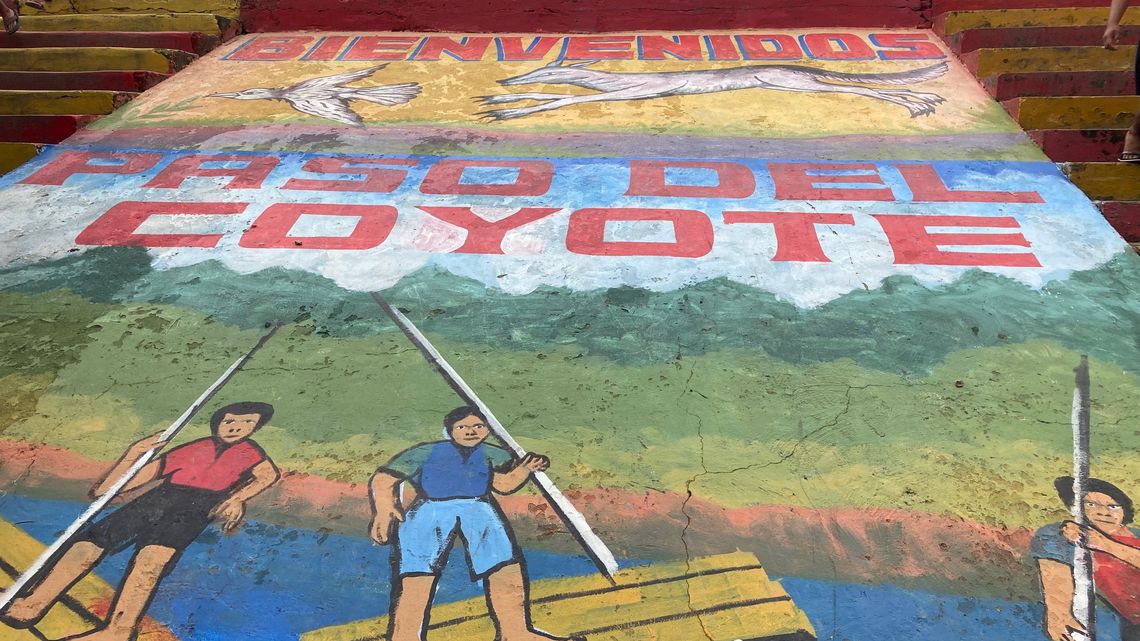

Tapachula is a living symbol for this regime, which no longer offers protection and security to people in need. Instead, state authorities perceive refugees and migrants primarily as a security risk that has to be detained. This is the lived experiences of our partnerss, regardless of whether they have travelled to Tapachula from Greece, Mali or El Salvador. We are in Mexico at the invitation of two local organisations, Voces Mesoamericanas and Centro FrayMa. Together we want to discuss what we can do to counter the ever-increasing violence against refugees and migrants, but also against the organisations that support them. Tpachula is a hub of refugees and migrants on its way to North America. The number of civilian and military border authorities has increased massively in recent years. As we witness during a field trip, they are not only patrolling at the Guatemalan border, but have set up countless posts along the transit routes far into the north. They check anyone who arouses suspicion – and detain everybody that lacks valid papers. Brenda from Centro FrayMa tells us she has documented countless pushbacks and filed complaints against them. So far without success.

Tapachula has become a "Ciudad carel" for migrants and refugees, as the way from there to the USA is increasingly cut off. This is an effect of the externalisation of the US-border regime, which has gained momentum under Trump. With a mixture of threats and financial aid, the US has turned Mexico into a highly armed outpost of Fortress USA. The fight against migrants and asylum seekers is no longer limited to the border region between the US and Mexico. It is waged along the entire migration routes through Mexico, and especially at the southern border, where most people are now intercepted. Since December 2018, when President Lopez Obrador took office, Mexican authorities have detained 846,477 people fleeing the country. 114,000 people were deported from Mexico last year alone. Most of those have experienced violence, Sandy from Voces Mesoamericanas tells us.

Even caravans no longer offer protection

In order to protect themselves, migrants in Central America and Mexico have been forming large groups, the caravans, in the last years. A week before our arrival, a particularly large group of around 6,000 people set off from Tapachula – materializing an exodus from Central America that has been increasingly affecting Central America. 400,000 migrants and refugees come to or through Mexico every year. They leave their homeland for many reasons, be it violence, displacement, climate change or the search for a better life. However, the caravans hardly get far. The most recent one was stopped by military forces only a few hours after it had left Tapachuchla. Some of the migrants got papers granting them a one-month stay in Mexico. But after they moved on, other security forces questioned the authenticity of the papers and have since prevented the people from moving on. Doubting the authenticity of papers, as well as deliberately destroying them, is a common practice of state authorities in Mexico, as are arbitrary arrests, detention of people for weeks, pushbacks and racially motivated violence, especially against indigenous and black people.

Tapachula is everywhere

As terrible as the accounts of experiences in Tapachula are, they are not unique. On the contrary. At the workshop, Anastasia from our Greek partner organisation Equal Rights Beyond Borders reports on her work in the deportation detention centre in Corinth on the Peloponnese. Detainees call it "the fridge" because people are imprisoned there for months and years suffering from very bad conditions and lack of legal assistance. Moctar from Alarmphone Sahara has documented countless pushbacks from Algeria to Niger, where people are abandoned in the middle of the desert. Indigenous women from San Cristobal tell us how their family members disappeared on their way to the USA. Thousands of refugees and migrants have fallen victims to criminal gangs or the deadly heat in the US desert in recent years.

Militarisation and isolation, disenfranchisement and impunity - it is striking how similar the contexts are in which partners of Brot für die Welt in Bamako and Beirut, on Kos and in El Salvador try to defend the rights of refugees and migrants. Despite the terrible experiences we share at the workshop: It gives strength to see that other organisations also continue to work under these difficult and often dangerous circumstances - whether they are fighting for the right to family reunification for refugees on Chios, saving people in the Sahara or strengthening the self-organisation of migrants in southern Mexico. The workshop focusses on sharing strategies, for example in working with local groups, in documenting human rights violations or in self-care. At the same time, we discuss how we can strengthen our forces by collaborating in the future. The first collaboration already takes place at the closing of the workshop, at the World Refugee Day. We hold a press conference with self-organised migrant groups in Tapachula, followed by a demonstration denouncing the injustice that refugees and migrants experience worldwide and every day. Brot für die Welt will continue to face this challenge together with its partners in the future. Promised.